2025 Energy Networks Australia Regulation Seminar: Hard Reset? Disruption, Transition and the Customer

Keynote regulator's address by AER Chair Clare Savage

Acknowledgement of Country

I want to start by acknowledging the Jagera and Turrbal people as the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which we meet today and their enduring connection to this land, water, and community in Meanjin, the place of the blue water lilies.

Introduction

Thank you to Dom and the ENA for the invitation to speak again today. Thank you also to Lawrence Slade, for your keynote address.

Context

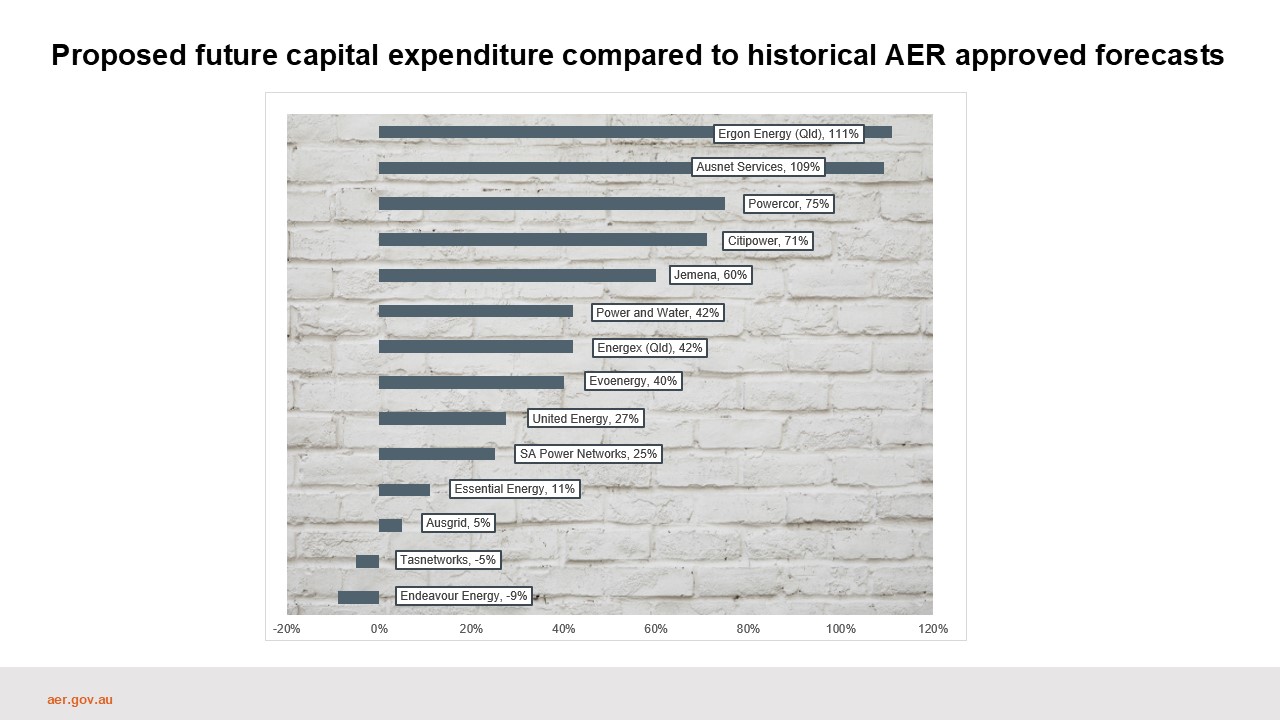

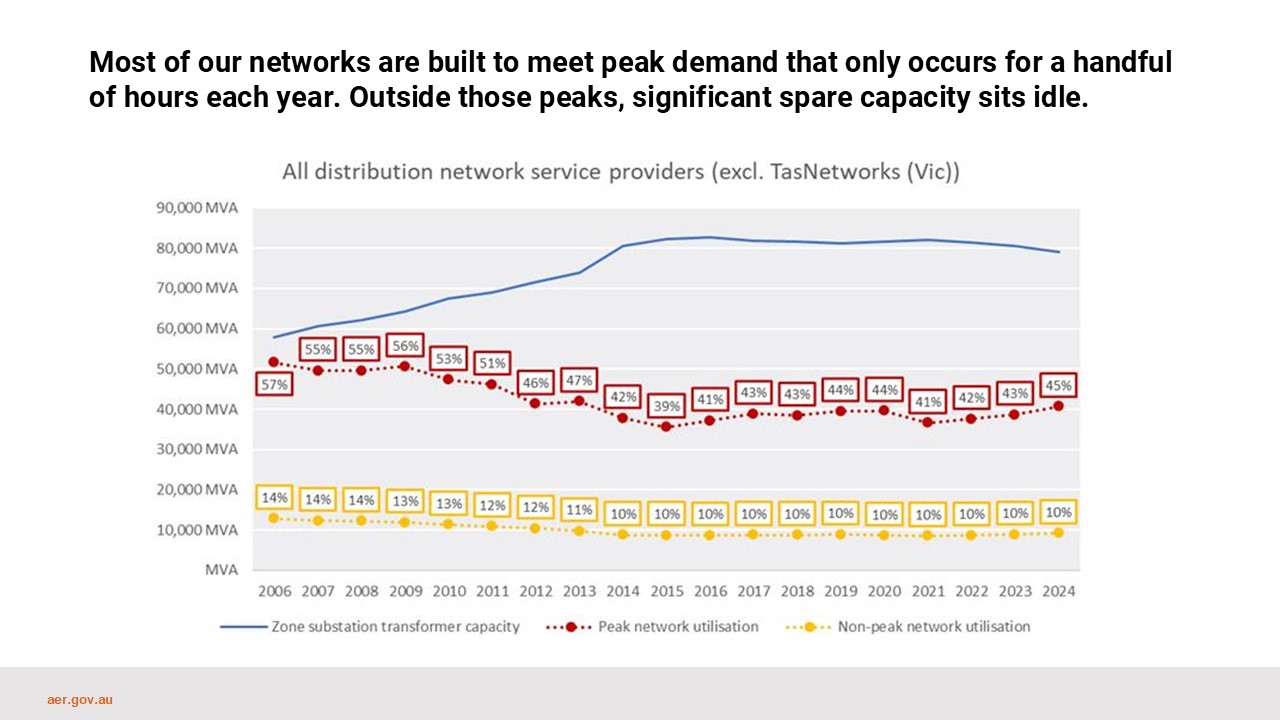

A year ago, I stood on this same stage and, for the first time (publicly at least), uttered the words “wall of capex” and stressed that “before we build more network, we need to use more network” to improve network asset utilisation.

Some people were offended that I drew attention to the significant increases in capex that network businesses have been proposing in their five-year regulatory determinations. But let’s make no mistake – the “wall of capex” is real. The initial proposals from the Victorian distribution businesses received late last year further support this.

Others were perhaps listening more carefully though and heard me also say that there are lots of prudent and efficient reasons why network capex might be increasing – not least of all because of the need to build more resilient networks (resilient to both increasing climate risks and cyber threats), and to accommodate more consumer energy resources and increasing electrification over the coming years.

But, as we all know, consumers don’t want higher energy bills and so I was also clear last year that the AER has an open mind about how we break down the barriers to more efficient utilisation of network infrastructure to avoid this “wall of capex” bearing down on us.

Pleasingly, many in the room last year heard the opportunity in those comments.

Since then, I’ve had this t-shirt printed and the AER has engaged extensively on this question of how to improve network asset utilisation including through our initiative with “policy-led sandboxing” (which I will talk more about later).

If we can improve network asset utilisation, we can potentially lower the per unit cost of electricity – improving not only the productivity of our own sector but every sector of the Australian economy that depends upon electricity as a key input to production.

Importantly, we can also relieve pressure on Australian households.

Energy transition and customers

The energy transition is not some distant future scenario—it is here, happening now.

We’re all familiar with the meteoric rise of rooftop solar over the last decade and home batteries are beginning to take off now as well.

The Australian Government’s ‘Cheaper Home Batteries Program’ has apparently seen the installation of 20,000 new home batteries just in the last month with an average battery size of approximately 18kWh (I have a home battery much larger than that and it has wheels!).

Some level of orchestration of these distributed and consumer energy resources will be critical if we are to improve network utilisation and avoid unnecessary augmentation of the system.

But there really are only two ways to do this – to ensure that assets locate in sensible places and are dispatched or are storing energy for the benefit of the system as a whole – and it is via price signals that shift behaviour or it is via direct control of assets.

Without price signals or control or some combination of these - higher bills are a certainty.

For consumers, these changes aren’t abstract. They show up in energy bills, in the reliability of their power, and in how easy – or hard – it is to take part in the new energy economy.

The AER’s latest retail performance data tells us that energy debt remains a persistent problem, despite concessions and hardship programs.

The number of customers with debt more than 90 days old has increased and customers entering hardship programs are doing so with higher levels of debt than before.

This highlights why, even as we invest in tomorrow’s energy system, we must not lose sight of people who are struggling today.

Many households are facing difficult choices about whether to heat, cool, or power their homes in the ways they want and need - emphasising the importance of balancing the urgency of the transition with the responsibility to protect consumers from avoidable long-term costs.

We are focused on improving consumer outcomes and ensuring the regulatory framework works for all customers – not just those able to invest in new energy technologies, but also those who are vulnerable and at risk of being left behind.

Today, I want to focus on two themes:

What is the potential role of networks in improving network asset utilisation via orchestration and delivering for customers and what is the role of the market and competition?

What is the role of networks?

Our energy system, and its myriad of rules and regulations, were designed to correct for the market failures of the past.

A critical question we must consider is whether the source and nature of market failure remains constant in a rapidly evolving energy system.

Structural separation in the supply chain and the introduction of competition in generation and retail was critical to driving the efficiencies we have benefited from in recent decades.

Yet, in an increasingly decentralised system, the separation between networks and generation/retail can make it more difficult to get incentives to align in the interests of the evolving system and customers.

We see this play out when retailers choose to focus on managing wholesale market risk exposure but can refuse to take the role of managing network cost risk for the customer.

And why is it that we now expect huge volumes of solar and storage to be funded by customers in the form of “behind the meter” assets? Why is this not on a business’ balance sheet?

The existing grid including its generation assets were founded on “collective” shared assets and sharing of costs.

The consequence is that we are creating a two- tier system of energy costs.

Those who rely solely on the grid assets will be paying more for electricity than consumers with a house/garage who have generation and storage assets, subsidised by other consumers or taxpayers.

In fact, recent analysis by the ACCC says this is already the case. Renters and/or those in premises without an available roof or without access to capital are likely to pay proportionately more of the costs of the grid that remains available to everyone.

The move to a decentralised system presents a number of potential coordination failures.

In a well-functioning market, individual actors pursue their own interests and the market mechanism aligns those interests to produce efficient outcomes.

But in increasingly complex systems (like our energy system) with orders of magnitude more ‘system nodes’, individual rational behaviour can lead to collectively suboptimal system level outcomes because actors struggle to coordinate their decisions; no single party has the mandate or incentive to solve the coordination problem; and/or critical information is fragmented or unavailable.

As the energy system decentralises, networks play a pivotal and increasingly complex role in both the emergence and resolution of market failures.

As monopoly providers of essential infrastructure, decisions around access, connection, pricing and system design have far-reaching implications for competition, participation and efficiency particularly in downstream markets where new business models, service providers and consumer offerings are beginning to emerge.

In some cases, current settings may inadvertently entrench coordination failures, create entry barriers or embed inefficient cross-subsidies that distort market outcomes and limit consumer choice.

As mentioned, one of the most persistent structural challenges in the transition is the limited utilisation of consumer-side flexibility or orchestration of consumer energy resources.

While the deployment of batteries, smart devices and controllable loads is increasing alongside a decade of network tariff reform, there is often no coherent mechanism to enable access, coordinate participation or consistently value these resources across the wholesale, network, and retail layers of the system.

This is more than a technological gap, and in some part, reflects weak alignment of incentives across system actors, information asymmetries and in some cases, restricted access to the infrastructure and data needed to support orchestration.

At the same time, networks are also uniquely placed to help address these failures for example, by supporting shared visibility frameworks, enabling open access to orchestration platforms or procuring non-network alternatives like flexibility services. However, the appropriate role for networks is not self-evident.

Emerging models for coordination and contestable delivery involve material uncertainty around benefits, risks and optimal institutional arrangements.

Policy-led sandboxing

This is where regulatory sandboxing becomes essential to test underlying assumptions, trial transitional mechanisms and evaluate the conditions under which different actors (networks, retailers, aggregators, communities) can deliver system value.

Structured trials can inform which functions should rest with the regulated monopoly, which are better suited to competitive provision and how roles and responsibilities might evolve over time.

In this way, sandboxing becomes a critical tool for navigating uncertainty, addressing structural inefficiencies and enabling a more dynamic, decentralised and consumer-centred energy system.

The Productivity Commission recently noted that:

“policymakers and regulators must further develop their sense of being stewards of the regulatory systems they manage – they must take greater account of the impact of their decisions on business dynamism and be proactive rather than reactive and excessively risk averse.”

In that same spirit, late last year I convened a large and diverse stakeholder group to discuss how policy-led sandboxing could be used to accelerate CER and DER access, deployment and orchestration.

In the first workshop we received incredibly useful feedback which helped us refine the problem definition, policy issues and key principles.

The second workshop focused on unpacking the exact policy questions we want solved and the principles to guide policy-led sandboxing trial design.

It was agreed that policy-led sandboxing could help explore the following policy questions:

1) What types of relationships (between distributors, retailers, co-operatives, embedded networks, third parties and customers) and/or ownership models for DER/CER could better enable access to, and deployment and orchestration of, DER/CER?

2) How might the benefits of deployment and orchestration of DER/CER be valued, and that value accrued and distributed, to deliver a least-cost energy system? What role could a Distribution System Operator play?

3) Which model(s) for access to, and deployment and orchestration of, DER/CER build consumer trust and social licence for mass adoption and orchestration of DER/CER?

Instead of waiting for sandboxing trial applicants, we’ve proactively identified areas where the system urgently needs to evolve and invited large-scale, in‑market trials.

The sandbox gives all participants – including networks – the ability to trial new ideas in a controlled way.

In response to our call out for trials, Ausgrid has applied to trial Community Power Networks in two regions in NSW.

The trial proposes to enable Ausgrid to purchase and own battery assets and potentially solar generation assets across the two trial areas.

The locations of these assets would be informed by Ausgrid’s spatial energy plan that will map out the current energy loads, network constraints and consumer energy resources assets in the trial locations, and identify the optimal locations for future consumer energy resources.

The trial will allow increased orchestration in managing these assets by pooling surplus solar from residential and commercial rooftops into batteries to enable redistribution during the evening peaks, to benefit all customers in the local area – not just those who are in a position to install these assets themselves.

As Ausgrid intends to control these assets, it will also enable them to provide services to the market, such as selling on the wholesale market and providing ancillary services.

Ausgrid expects this will generate value, which it proposes will be delivered to all consumers in the trial area through a dividend payment.

If successful, the trial may lead to increased solar network capacity and reduced emissions. Avoided network augmentation and the distribution of dividends to customers may also result in lower costs overall.

Now the prospect of this trial is likely to freak a lot of people out.

But this trial could be a valuable test of how networks may be able to open new pathways in the energy transition - helping to prove what works and what doesn’t, while leaving space for others to follow.

But these opportunities also come with risks.

We need to understand the potential changing nature of market failures as the energy system evolves and ensure any regulated networks trialling services that may ultimately be better delivered by competitive markets don’t distort the market or crowd out the potential for competition.

We will consult on this application and, if approved, ensure adequate protections are in place.

But regulatory sandboxing alone won’t be enough to understand the role of networks and competitive markets in a least-cost future energy system.

We also need to ask fundamental questions about the future of network regulation itself:

- What is the right balance between incentive-based regulation and explicit standards for conduct and performance?

- How do we appropriately incentivise non-network solutions?

- How do we create access arrangements for key platform services that underpin and enable new services, like putting EV chargers on power poles?

- And how do we streamline connection processes so they are faster, more transparent, and efficiently priced?

These are some of the questions being considered by the AER in our ongoing work but also by the Australian Energy Market Commission in its upcoming review of network regulation.

We welcome this review and look forward to contributing our own learnings.

All of this work is part of a bigger picture: evolving networks from static infrastructure providers into dynamic platforms for energy services.

That is a big shift, but one we must make if we are to increase network asset utilisation and unlock the full value of consumer energy resources.

And what about markets?

I’ve talked a lot about the role of networks. But we need to understand where markets can thrive in the evolving energy system to drive innovation, offer choice and deliver products that reflect the diverse needs and preferences of consumers.

If networks are allowed to take on new roles or offer new services where market provision may be sub-optimal, we still need to ensure that these activities do not unfairly disadvantage competitive providers.

That’s why ring‑fencing obligations exist and remain critical.

One current example is the ring‑fencing waiver application related to EV charging infrastructure from CitiPower, Powercor, and United Energy, which we are considering carefully.

We have to balance the potential benefits of networks providing certain services in certain locations with the need to maintain effective and efficient competitive markets.

This is also reflected in our Compliance and Enforcement Priorities for 2025–26, where we have explicitly committed to promoting competition and ensuring safe, reliable infrastructure by ensuring compliance with connection and ring‑fencing obligations.

These obligations are there to protect the integrity of the market, ensuring consumers benefit from innovation and choice.

And we want to work with networks to ensure compliance is straightforward and supports the outcomes we all want: affordable, reliable, and safe energy services that are responding to a changing market.

The role of prices

I’ve talked a lot today about the potential role for networks and/or markets in orchestrating consumer energy resources to improve network utilisation and lower energy system costs.

I also flagged this orchestration could be delivered by direct control of assets but also by behaviour change in response to price signals.

Yet network pricing reform has become a somewhat vexed topic of late. As we outlined in our submission to the AEMC’s pricing review, tariff structures must do more than reflect cost – they need to support efficient system use, encourage flexibility, and minimise unnecessary investment.

That means providing price signals that reflect when and where the network is under strain – but also asking sharper questions about who those signals are sent to.

In many cases, retailers or aggregators may be better placed than individual consumers to manage risk, optimise across portfolios and translate signals into action with the assistance of technologies.

If markets don’t want to accept or manage these risks though then this may at least answer one critical question.

At the same time, we can’t ignore the role that residual network cost recovery plays in shaping and often distorting these network price signals.

Today, most customers still face relatively low fixed network charges, with residual costs, which are sunk and not avoidable, recovered through variable charges.

This can blur the price signal, affect the efficiency of demand response and embed inequities between consumers, as those with consumer energy resources can arbitrage away from their contribution toward these residual sunk network costs.

If network pricing (as opposed to direct control of assets) is to play a meaningful role in a more dynamic system, we need to ensure residual cost recovery does not distort consumer behaviour or undermine efficient investment decisions – and ensure that the value created by consumers who provide system flexibility is fairly recognised and shared.

Efficient pricing and improved network visibility are not just technical upgrades, they are foundational to the future operation of the distribution system.

As new models like Distribution System Operation emerge, there will be a growing need for more active, real-time management of local networks including coordination of exports, and the flexible loads of smart appliances.

This shift puts networks squarely at the interface between physical infrastructure and market participation, between system needs and consumer preferences. Increasingly, networks will be enabling a new layer of system functionality that will require shared data, signal translation and the capacity to host an array of contestable service providers.

These system-level design questions are still live.

Through the Commonwealth Department’s current consultation process focused on redefining roles for market and power system operations, big decisions are ahead:

- What roles should networks play in this more decentralised future?

- How do we clearly separate monopoly functions from contestable ones?

- And what kind of platform is needed to enable participation, ensure transparency and share value, without entrenching market power or losing from innovation?

Network pricing reform and improved operational visibility are two essential building blocks on this path.

Pricing can help establish credible value streams for flexibility and guide efficient investment decisions.

Visibility ensures competitive neutrality, supports planning, including connections processes, and allows all participants to engage on fair terms.

These aren’t just regulatory tweaks, they are preconditions for a system that works, and networks are at the core of making that possible.

Conclusion

The energy system we all grew up with is being reshaped before our eyes.

Consumer energy resources, electric vehicles, new technologies, and the realities of climate change are transforming how energy is produced, transported, and used.

Networks have a vital role in delivering a system that serves consumers now and into the future.

That means not just building more infrastructure, but orchestrating energy flows, enabling innovation, and making efficient use of what we already have – both behind and in front of the meter.

It means working with new partners and technologies in ways that protect consumers and preserves reasonable market access.

Our goal is not simply to say “no” or “yes” to proposals—it is to create a framework that allows good ideas to flourish while protecting consumers from unnecessary costs and risks.

The transition is urgent, but urgency cannot be an excuse for inefficiency or for undermining competition - IF and where competition can deliver a lower cost energy system.

We must consider the nature of the evolving energy system, understand any new sources of market or regulatory failure and regulate (or de-regulate), where required, to address these failures.

Being willing to try different things will be an inherent part of getting this right for consumers.

Thank you for your time today, and for the work you are doing to support this transition.